“The Wisdom of Crowds” is one of the driving principles of Web 2.0. The idea, explored in James Surowiecki’s influential book, is that decisions made by large numbers of people together are better than decisions that would have been made by any one person or a small group. This principle has powered the wide adoption and success of tools including including Google, collaborative filtering, wikis, and blogs.

One common technique, following the Wisdom of Crowds principle, is the use of ratings. The hope and expectation is that by enabling large numbers of people to express their opinion, the best will rise to the top. In recent years, rating techniques have been put into practice in many situations. The learnings from real-life experience have sometimes been counterintuitive and surprising.

The failure of five-star ratings

Many sites including Amazon, Netflix, and Yahoo! used five-star ratings to rate content, and this pattern became very common. Sites hoped that these ratings would provide rich information about the relative quality of content. Unfortunately, sites discovered that results from the 5-point scale weren’t meaningful. Across a wide range of applications, the majority of people people rated objects a “5” – the average rating across many type of sites is 4.5 and higher. Results from YouTube and data from many Yahoo sites show this distribution pattern.

Why don’t star ratings provide the nuanced content quality evaluation that sites hoped for? It turns out that people take the effort to rate primarily things they like. And because rating actions are socially visible, people use ratings to show off what they like.

How to use scaled ratings effectively

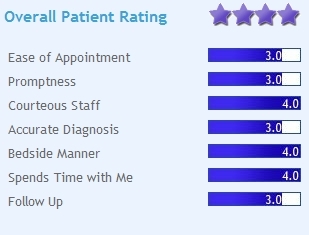

So, is it possible to use scaled ratings effectively? Yes, but there needs to be careful design to make sure that the scale is meaningful, that people are evaluating against clear criteria, and that people have incentive to do fine-grained evaluation. Examples of rating scales with more and less clear criteria can can be found in this Boxes and Arrows article – the image from that article is an example of a detailed scale.

There are tradeoffs between complexity of the rating criteria and people’s willingness to fill out the ratings. Another technique to improve the value of scaled ratings is to weight the ratings by frequency and depth of contribution, as in this analysis by Christopher Allen’s game company. This techniques may be useful when there is a relatively large audience whose ratings differ in quality.

Like

The simpler “thumbs up” or “like” model, found in Facebook and FriendFeed has taken precedence over star ratings systems. This simpler action can surface quality content, while avoiding the illusory precision of five-star ratings. The vote to promote pattern can be used to surface popular content. This technique can be used in two ways – to highlight popular news (as in Digg) or to surface notable items in a larger repository.

Several considerations regarding the “like” action: this sort of rating requires a large enough audience and frequent enough ratings to generate useful results. In smaller communities the information may not be meaningful. Also, the “like” action indicates popularity but not necessarily quality. As seen on Digg and similar sites, the “like” action can highlight the interests of an active minority of nonrepresentative users. Or the pattern can be subject to gaming.

Another concern is the mixing of “like” and “bookmark” actions. Twitter has a “favorite” feature that is also the only way for users to bookmark content. So some number of Twitter “favorites” represent the user temporarily saving the content, perhaps because they disagree with it rather than because they like it! Systems that have a “like” feature should clearly differentiate the feature from a “bookmark” or “watch” action.

The risks of people ratings

Another technique that sites sometimes use, in the interest of improving quality and reliability, is the rating of people. Transaction sites such as Ebay use “karma” reputation systems to assess seller and buyer reliability, and large sites often use some sort of karma system to incent good behavior and improve signal to noise ratio.

The Building Reputation Systems blog has a superb article explaining how Karma is complicated. The simplest versions don’t work at all. “Typical implementations only require a user to click once to rate another user and are therefore prone to abuse.” More subtle designs still have an impact on participant motivations that may or may not be what site organizers expect. “Public karma often encourages competitive behavior in users, which may not be compatible with their motivations. This is most easily seen with leaderboards, but can happen any time karma scores are prominently displayed.” For example, here is one example of karma gaming that affected even in a subtle and well-designed system.

Participant motivations, reactions, and interactions

When providing ratings capabilities for a community, it is important to consider the motivations of the people in that community. In the Building Reputation blog Randy Farmer talks about various types of egocentricand altruistic motivations. Points systems are often well-designed to support egocentric motivations. But they may not be effective for people who are motivated to share.

Adrian Chan draws distinctions between the types of explicit incentives used in computer games, and the more subtle interests found in other sorts of social experiences, online and off. People have shared interests; people are interested in other people. The motivations come not just from the system in which people are taking these actions, but from outside the system – how people feel about each other, how they interact with each other.

In a business environment, people want to show off their expertise and don’t want to look stupid in front of their peers and superiors. They may want to maintain a harmonious work environment. Or in a competitive environment, they may want to show up their peers. These motivations affect the ways that people use ratings features as well as how they seek and provide more subtle forms of approval, like responses to questions in a microblogging system.

Thomas Vander Wal talks about the importance of social comfort in people’s willingness to participate in social systems, particularly in the enterprise.

People need to feel comfortable with the tools, with each other, and with the subject matter. The most risky form of ratings, direct rating of people, typically reduces the level of comfort.

Depending on the culture of the organization and the way content rating is used, content rating may feel to participants like encouragement to improve quality, like a disincentive to participation, or like an incentive to social behavior that decreases teamwork. Even with good intentions and thoughtful design, the results may not be as anticipated. In that case, it is important to monitor and iterate.

Scale effects

The familiar examples of ratings come from consumer services like Amazon, Netflix, and Facebook, with many millions of users. With audiences as large as Amazon’s, there are multiple people willing to rate fairly obscure content. In smaller communities, such as special interest sites and corporate environments, there are many fewer people: hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands. While the typical rate of participation is much higher – 10-50%, rather than 1-10%, that is still many fewer people. With a smaller population, will there be enough rating activity to be meaningful. If an item has one or two ratings, what does this mean? Smaller communities need to assess whether the level of activity generates useful information.

Summary

Ratings and reputation systems can be very useful at surfacing the hidden knowledge of the crowd. But their use is not as simple as deploying a feature. In order to gain value, it is important to take into account lessons learned:

* Think carefully about the goal of the ratings system. Use features and encourage practices to achieve that goal

* Use an appropriate scale that addresses the goal

* Consider the size of the community and the likelihood of useful results

* Consider the motivations and comfort level of the community and how the system may affect those motivations and reactions

Then, evaluate the results. The use of a rating system should be seen not like a “set and forget” rollout, but as an experiment with goals. Goals may include quantitative measures like the volume of ratings and the effect on overall level of contribution, as well as qualitative measures such as the effectiveness of ratings at highlighting quality content, the effect on people’s perception of the environment, and the effect on the level and feeling of teamwork in an organizational setting. Be prepared to make changes if your initial experiment teaches you things you didn’t expect.

For more information

The Building Reputation blog, by Randall Farmer and Bryce Glass, is an excellent source of in-depth information on this topic. The blog is a companion to the O’ReillyBuilding Web Reputation Systems.

Other good sources on this and other social design topics include:

* Designing Social Interfaces book and companion wiki, by Christian Crumlish and Erin Malone.

* Chris Allen’s blog

* Adrian Chan’s blog