Aphrodite and the Rabbis, by Burton Visotzky, professor of Midrash at Jewish Theological Seminary, explores how Rabbinic Judaism, the dominant strain of Judaism for 2000 years after the destruction of the temple, developed in a matrix of hellenistic Greco-Roman culture under the Roman empire.

Examples: Hellenistic literary scholarship was based on study and commentary of the 24 books of Homer; the Rabbis used very similar modes commenting on the books of the Hebrew Bible; and they even shoe-horned the count of books in the canon to equal 24 in order to parallel the Homeric canon. The Passover seder was modeled directly on the hellenistic “symposium”, an intellectual seminar and feast interspersed with alcohol, dishes with dipping sauces, and music.

In focusing on what Rabbinic Judaism inherited from Hellenistic culture, Visotsky does not explore what is different. The symposium evening ended with courtesans entertaining the guests; that is not part of the Passover haggada. The book shows interesting literary similarities, but does not attend to the dramatic and presumably deliberate difference in which the Rabbis assertively avoid structures based on categories and sequence; the Talmudic forms are relentlessly digressive and associative. The book tells stories of interactions between Rabbis and various Roman figures; but stays away from the extensive talmudic material about avoiding contact and familiarity with pagans and the props and rituals of paganism.

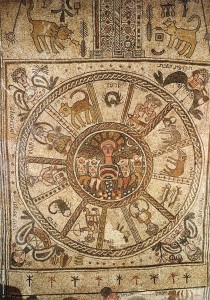

The book provides evidence that Jews in the Roman empire were much more familiar with Aramaic and Greek than Hebrew. And it shows how early synagogue architecture was extraordinarily similar to the temples and churches down the street in Roman empire towns; and how the synagogue art was strikingly similar, including ubiquitous images of the Zodiac, and even images of Zeus/Apollo riding his 4-horse chariot across the sky.

In describing the material culture of Jews in the Roman empire, though, the book has very little information about how Jews lived outside of the Rabbinic academies, even how much connection there was (or wasn’t) between the elite scholars in the academy, elaborating ideas about normative ritual practice; and what Jews actually did. In one of the apparently few areas where there is evidence, the book inventories synagogues to assess how many follow the Rabbinic dictum to face toward the East, toward Jerusalem. The result is inclusive.

Last and least, the tone of the book is informal and jocular, which this reader found mildly distracting. Overall, I would recommend the book for those who are interested in the subject matter.

Visotsky argues that even as the Talmudic era Rabbis define themselves politically and religiously in contrast to the dominant culture, they were at the same time deeply shaped by the culture.