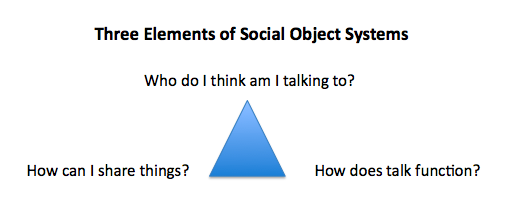

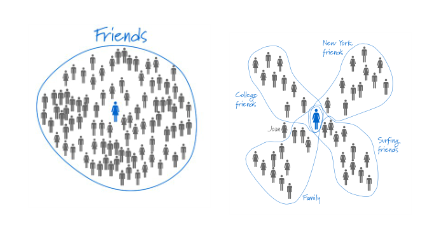

There is no such thing as “friends”. That’s the most powerful conclusion in an excellent presentation about in-depth research by Paul Adams, UX researcher at Google. Most people tend to have 4-6 groups of friends, each of which has 2-10 people, and there is typically very little overlap between them. These friends represent different life stages and interests. A person’s large “friend list” on a service such as Facebook or Twitter actually consists of a handful of close friends and family members, in different groupings, plus a much larger number of casual friends and acquaintances.

As Mary Walker observed on Twitter, “Each person=many roles (family friends career hobbies) but social networks suck @ helping ppl manage this.” Mary was summarizing this post by Deanne Leblanc. The mismatch between the affordances of social tools and the shape of our social lives has been observed by many – and Adams’ research quantifies that mismatch.

In software design, the common usage patterns need to be very strongly supported – and in Facebook it’s definitely not. Paul Adams reaches powerful conclusions that would result in social software designs very different from Facebook, which has very poor control over what to share with whom, and poor control over how to present oneself within different social contexts.

Follow up questions: social boundaries

The presentation is excellent, and the research looks well-done – and I also have some follow-up questions about the results. The presentation concludes that there is very little overlap between groups of friends. But, I wonder about that overlap. What is the role of the people who span groups, co-workers who share an interest in a sport, fellow parents who are involved in local politics? From the perspective of the spread of information, culture, action, do boundary-spanners have extra influence?

Also, the presentation observes that people’s friends change as their lifestage and interests change – but the presentation focuses on the static picture at any point, rather than the changes. How do these changes happen? How often do social connections play a role in the changes? Focusing on the changes and transitions, rather than on the patterns of stasis, might yield interesting insights on secondary patterns to support.

The example in presentation, about sharing that unintentionally crosses boundaries, is about a young woman who comments on photos of her friends in a gay bar; these risque photos are exposed to 10-year-old kids she teaches. In Twitter, Paul acknowledges that the friends being gay isn’t the problem, sharing pictures of adult sexuality with kids is the problem – and editing the presentation to make that distinction clear would be good to do.

In that case, partitioning is the right thing to do. But there are many other examples of sharing where the problem isn’t sharing stuff that is inappropriate for a social context, but where it’s uninteresting to some . Is it possible to design a system that makes it easier to improve the signal to noise ratio without hiding information that doesn’t need to be hidden.

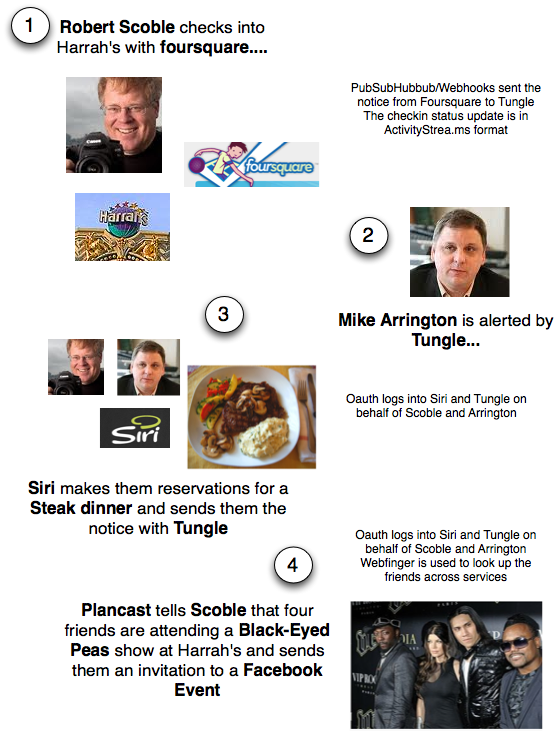

The presentation talks about the new social web architectural pattern where one takes ones friends with them across the web – for example, on cnn.com, you see the stories your friends liked and commented on if you are logged into Facebook. But how should this pattern work, given that “friends” are not a single group. For a person long past highschool, is seeing the opinions about a high school acquaintance on a news story a benefit or a drawback? (This example is theoretical, apologies to any HS friends who may be reading this!)

One common theme among this set of questions is about the boundaries between strong and weak ties – how can software do a better job of supporting strong ties, while enabling a semi-permeable membrane for people to people and communication to cross those boundaries. Of course (and the presentation does a good job of reminding) is that the relationships are amongst people, not tools. Boundaries are shaped and reshaped by people in our interactions; tools can help or hinder but they don’t create or destroy.

A different social network

Recently there’s have been rumors that Google is going to come up with a new social network that is a Facebook clone. I really hope that Google doesn’t simply clone Facebook, and instead that they use the insights in Paul Adams’ research to make social network tools that are different from Facebook, and better suited to how people’s social networks function.